Hello everyone, I am very frustrated and angry at myself, so I’ve decided to blow off some steam by spending some time writing this essay. It will be incoherent, please bear with me.

[Warning: There are spoilers abound. However, I don’t believe they would hinder the reader from exploring these works—in fact, I hope they spark some mild interest in them.]

Though vastly different stories set in vastly different places, concerning completely different demographics, I believe Onani Master Kurosawa and Crime and Punishment share many core themes, mainly on those of guilt, justice, nihilism, and the nature of ethics.

The nature of this essay will be free-form, with little to no prior planning—I’ll type whatever comes to mind and cover what I think is important. Mind you, my memory is not so good, so I’ll probably get some details from both stories wrong in my analysis, but I hope I’ll be able to cover the overarching connections between them.

Onani Master Kurosawa

Onani Master Kurosawa is a doujinshi (self-published work) written by Takuma Yokota and illustrated by Katsura Ise. Set in Japan, it follows the story of ‘Kurosawa’, a reserved, cynical high school student with a perverted hobby: every day after school, he would go into the girls’ bathroom and masturbate. However, he would one day be discovered by a small girl named Kitahara. From there, she forces him into a contract—in return for keeping his depraved habit a secret, he would be tasked with carrying out ‘revenge’ on every student that has bullied her (all of which involves him ejaculating on their belongings in one way or another).

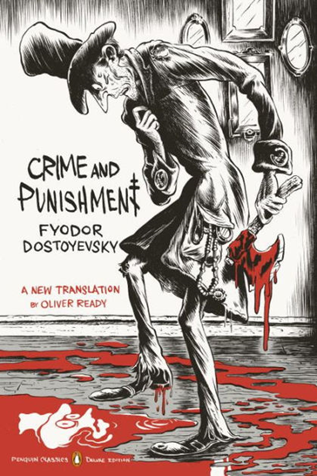

Crime and Punishment

Dostoevsky’s ‘Crime and Punishment’ is a novel by the highly acclaimed Fyodor Dostoevsky. Set in St. Petersburg, Russia, it follows the story of Rodion Raskolnikov, a dishevelled and frustrated university dropout—destitute and out of funds, he lives alone in a cramped flat, with little money to spare for daily needs. In this state of poverty, he fixates on a long-standing theory of his—the possibility of ascending culture, rules, and ethics, for the sake of one’s own gain (or in his words, to ‘become a Napoleon’). Desperate to test this theory—and in need of money—he visits a local pawnbroker—a vile, cruel old lady that literally everyone hates—and murders her with a hatchet. Unfortunately, the old lady’s sister was in the apartment at the time, and he is forced to kill her too. From there, he is forced to live with the sin of double murder, and struggles to keep himself psychologically intact.

In terms of the larger premise, one can easily gleam a few similarities—both largely concern the concealment of a depraved act, in Kurosawa’s case being his demented masturbation habits, and Raskolnikov his implications in the old woman’s murder. However, I largely characterise the journeys featured in both stories as that of wading through a sea of degeneracy—one of their own making—in search of redemption/some sort of moral light.

The Protagonists

To get some good context for their journeys though, I want to make a brief overview of their characters.

Both Kurosawa and Raskolnikov are cynical and critical in nature—they view their surroundings with scepticism, and regard many elements of their lives with disdain. In Kurosawa’s case, he despises the general demeanours of his fellow classmates, and separates himself from what he deems to be the norm. Raskolnikov too holds a level of resentment for his surroundings—he dislikes talking to people in general, resents his own poverty, and most especially resents the old pawnbroker.

It is in this resentment and separation from the affairs of the normal man that one gleams another striking relationship between the two: both of these young protagonists have superiority complexes (or at least in the case of one, seeks to achieve superiority). Regarding Kurosawa, it should be noted that whenever he masturbates in the girls’ bathroom, he imagines himself copulating with a specific girl in his class, and all of these instances involve some sort of power play or another, with Kurosawa being the dominant figure, and his unfortunate victim the submissive one. Notwithstanding this aspect of his character, the superiority he feels to the rest of his fellow students is also made clear in a good amount of his inner dialogue—he regards most of the characters around him as foolish and simple-minded, and makes great efforts to separate himself from them. Raskolnikov too—at least concerning the intellectual aspect of his character—plays with the idea of ascending oneself beyond the norm, a mental exercise that ends with his grisly crime. And no wonder he commits the crime—on the verge of starvation, jobless, and unable to continue his education due to his financial troubles and personal troubled feelings, he feels anything but strong. In this way, the murder of the old pawnbroker was a desperate attempt to grasp some semblance of control over his situation.

All in all, we’ve established these two young men as detached, over-rationalised individuals with—at least—a strong desire to separate themselves from the norm.

And just like any story, the plots surrounding them both contain a core conflict—a situation that challenges the integrity of their characters, from their sense of individuality, the validity of their over-rationalised methods, and their views of the world. Kurosawa, having been found out by Kitahara, is severely limited in his masturbatory autonomy, effectively being used as a dog for Kitahara’s resentment-fuelled operations. Raskolnikov, though successful with his murder and having gotten away with any suspicion in his implications with the crime, is tormented by indescribable feelings of guilt—the kind that no matter what he does, cannot be rationalised away. In committing the murder, he effectively alienates himself even further from the world, and throughout the book struggles with figuring out how he’s supposed to conduct himself in the world.

Some Key Differences

Before I approach the similarities of their overall plots, I want to cover a key difference between the two, starting with Onani Master: in that Onani Master is, at its core, a bildungsroman (coming-of-age story). Beginning the story as a cynical teenage high schooler, he finds himself associated with a whacky assortment of students—the vengeful (but small and kind of cute) Kitahara, the eccentric otaku Nagoka, the quiet fat otaku Pizza (I forgot his actual name), and the core love interest Takagawa, of whom plays an immensely important role in his development. Much like Raskolnikov, you will find interest in viewing Kurosawa as two characters—the over-rationalised Kurosawa, and the human, affectionate and socialised Kurosawa. And it is this human aspect of Kurosawa that is severely under-developed in the start of the story, its growth and progression into maturation the core focus of his journey.

Raskolnikov, on the other hand, is depicted as already possessing these two aspects of his personality, and it is rather the continued conflict between these two sides that make his character so compelling throughout the book. While we’ve already covered the idea of his intellectualism and calculated thinking, he also exhibits the characteristics of an overly compassionate, self-sacrificing person. Such instances are littered all over the plot—him quickly tending to a drunk old man who had just been run over by a carriage, spontaneously donating all of his savings to the said man’s family, and past reports of him risking his life to save a child from a fire are examples of such behaviour. And often, it’s in the aftermath of these random acts of kindness that one can observe the conflicts between his rational side and emotional side—he immediately chastises himself after foolishly donating his money to the drunk man’s family, he desperately tries to stop his sister from marrying a man he knows she does not love, only to immediately turn to the rationale that he shouldn’t meddle himself with other people’s problems and contend that she should just do whatever she wants. This human side of him is already sufficiently developed, and—just a passing thought—perhaps he represents a possible future for someone like Kurosawa.

Supporting Characters

But I digress—let’s talk about Kurosawa’s and Raskolnikov’s stories. Like I mentioned, their stories are largely journeys towards redemption—or in better terms, towards a higher mode of moral being. For Kurosawa, it’s in the development of his relationships and joining the world, and for Raskolnikov the balance between intellectual thought and the seemingly unshakeable foundations of morality. However, such a journey is impossible without supporting characters, of which have an uncanny degree of resemblance between the works.

For starters, I would like to point out how both protagonists are flanked by characters that distinctly personify their over-rational resentful sides, and their humanistic compassionate sides.

On the side of compassion, Kurosawa has his love interest Takagiwa. An energetic and approachable girl, she meets him in the library one rainy day, and manages to strike up conversation with him, bonding over their mutual love for books. Though the polar opposite of Kurosawa, it is through her that Kurosawa begins to learn the joys of connecting with people, and the firsthand intensity of affection for another human being. Also of immense importance is her explicit role in the exact moment of his moral redemption, which we will get to at the end of the essay.

As for Raskolnikov, he has the young Sonya, the daughter of the drunk old man he saved. Her own family destitute, she was forced into prostitution in order to provide for them. However, though subject to a denigrating occupation, Raskolnikov notices in her a strong moral character—she brunts the shame of her work, is devoted to her faith, and ultimately strives to do good in spite of her lowly status. It is in her that Raskolnikov finds solace—especially approaching the end of the story—and much like Takigawa, also explicitly acts as a key in the moment of his redemption.

On the side of the destructive, Kurosawa is haunted and restrained by Kitahara. Small and meek, she is often the target of bullying and denigration from other classmates—this is her everyday reality. However, while inconspicuous at first with her squirrel-like looks, she slowly reveals herself to be a girl driven purely by resentment and the thirst for revenge. It is through her that Kurosawa is driven like a dog, and subconsciously begins to separate himself from his ‘hobby’.

And for Raskolnikov, he is pestered by the enigmatic but criminal Svidrigailov. He has a long history of sexual misconduct and unfaithfulness to his wife, sleeping with many of the maids in his household. Further dubious is the absence of shame for many of his crimes, most notably his raping of a 15 year old girl and his cool, reserved demeanour upon receiving the news that she had hung herself shortly after. Driven solely by lust and pleasure with a disregard for guilt or shame, Svidrigailov is a cruel depiction of Raskolnikov’s idea of the ‘Napoleon’. And understandably, Raskolnikov finds great revulsion in his character.

- An important note—that while characters such as Kitahara may not necessarily represent the cold intellectualism of Kurosawa’s character, her and Svidrigailov are connected in that their modes of being are inherently egotistical/for the sake of one’s own pleasures. And unsurprisingly, both stories cast such a mode of being as dysfunctional and prone only to destruction.

- In Kitahara’s case, she fails to grow as a person, and the bullying reaches such heights that in the pressure of it, she stabs herself in the hand and withdraws from school completely.

- And for Svidrigailov, in his failure to court Raskolnikov’s sister Dunya (who, mind you, has been in love with for a long time, beyond the beginning of the book) gives in to despair and shoots himself in the head.

Regarding other supporting characters (this will be the final one in terms of them), both Kurosawa and Raskolnikov are closely associated by what I would call their ‘well-adjusted others’.

Kurosawa is pestered by the energetic and friendly ‘Nagaoka’—he is notable for his broccoli-like hair and otaku interests (there are at least 2 Haruhi Suzumiya references in this book). Raskolnikov, on the other hand, has his close university friend Razumikhin, who too is energetic and friendly in nature.

Effectively, these ‘well-adjusted’ supporting characters act as a representation for what their counterparts—Kurosawa and Raskolnikov—could potentially become at the end of their self-actualisations. A common theme between these two stories are their best friends acting as surrogates in their life. Tragically in Kurosawa’s case, Nagaoka enters a romantic relationship with his love interest Takigawa, and while it causes a good amount of heart-ache initially, he comes to realise that a person as friendly and warm as Nagaoka was just what Takigawa needed, and Kurosawa failed to be. Similarly, Raskolnikov trusts his friend Razumikhin so much that at the deepest depths of his instability, he tells him to ‘take care of [his mother and sister]’ and to ‘never leave them’—he effectively enlists him as a surrogate son for their family. These two best-friend characters effectively anchor their troubled friends in reality and aid them throughout their turbulent journeys.

Finally, I want to discuss what I believe is the most important element between Onani Master and Crime and Punishment—the confession of their crimes. I’m too mentally taxed to gracefully discuss both stories at the same time in one paragraph, so I’m going to outline and pick them apart separately, and then bring them together in the final paragraph.

Onani Master - The Confession

It should be noted that in the middle of this story, Kurosawa, Kitahara, Nagaoka, and Takigawa (and Pizza-tan but who gives a shit about him) become acquainted with one another through a school trip to Kyoto, effectively grouping them up in one social circle.

Shortly after this, Kurosawa and Kitahara’s operations continue as normal. However, after summer break, it is revealed to him that Nagaoka and Takigawa had begun a romantic relationship, sparked during their interactions in cram school over the holiday. Falling into deep despair, it is also revealed that Kitahara is also heart-broken, for she too had affections for friendly Nagaoka. In their shared pain, the frequency and severity of their operations escalated—one could surmise that in this small portion of the story, Kurosawa had briefly personified Kitahara in his desire only to destroy what laid in his path. He was even tasked to cum on Takigawa’s belongings which—though performed out of resentment for life in general—only served to further his heartbreak.

However, in the midst of this tirade, he comes across a picture painted by Takigawa for art class—the theme was to draw ‘her most precious memory’. Unfurling the paper, what is revealed is an image of her, Kurosawa, and the rest of the social circle she had formed during their school trip. It is in this very instant that Kurosawa awakens to the extent of the damage he had done—his masturbatory tirade had tarnished the social relationships he had come to hold precious, going so far as to hurt and traumatise the girl he loved most.

Realising that more things precious to him would be at stake were he to continue, he—to the dismay of Kitahara—decides to come clean, and formally confesses his crime in front of the whole class.

Social stigmatisation and harassment towards him would ensue, however, contrary to how he may have reacted in the beginning, he does not take his punishment begrudgingly, and continues on with his student life with utmost diligence. (Note—it is also around this time that Kitahara stabs her hand and leaves school, a fitting inverse for Kurosawa’s personal development).

Surprisingly, even in the midst of this tormenting period, Kurosawa manages to mend his broken relationships, and even form some new ones, acquainting himself with classmates he had barely spoken to in the course of that year. Even more surprising is the fact that he manages to befriend Sugawa—one of Kitahara’s main bullies, and Kurosawa’s first victim—and actually enter a relationship with her 2 years later. These feats of socialisation—ones totally unknown to the Kurosawa of the beginning—are testament to his maturation.

Crime and Punishment - The Return to God

At the height of his torment, Raskolnikov confines in Sonia and confesses his crime to her—note that this is the first time he brings to light his crime to anyone, and it’s no surprise that Sonia would be the first he would consult.

However, the most compelling element of this scene is that, in spite of his heinous crime, Sonia immediately opts to bring attention to what Raskolnikov has done to himself. Compared to Raskolnikov, Sonia’s material living situation is near-unbearable—but the torment in his soul is magnitudes more painful than Sonia’s. “What have you done to yourself!” she wails, “There is no one… no one in the world now so unhappy as you!”

What this scene brings attention to is the idea that when Raskolnikov killed those two women, he had murdered a part of himself as well—the integrity of his soul, his place in the world as a human. Before Sonia, he lays out the rationale behind his act, and for the first time, clearly sees the foolishness of his ways. His utilitarian philosophy had destroyed his soul, snuffed out all that was good about him.

In the face of this, Sonia begs him to come clean of the crime, and in many points refers to such a confession as ‘returning to God’. Take note that his murder was a perfect one—there was very little suspicion in his involvement with the murders—and technically, he could live on a normal life and leave the crime behind. However, to Sonia, it is less a matter of practical living, but more so the salvation of his soul—if he is to return to the world and regain any hope of rebuilding his integrity as a human, confession is the only way.

And he does confess—walking into the police station, he anxiously slams his hands on the clerk’s desk and spells it out for everyone in the room: that he was the one that killed them. The court process followed, in which he unashamedly confesses his crimes before the judge and pleads guilty. The court takes his stance with surprise, astonished that he is willing to incriminate himself into the crime, and he is sentenced to 8 years of hard labour in Siberia.

To Siberia, Sonia followed, and in the final scene of the book, while he rested outside after a hard day’s work, he talked with Sonia and in her arms—for the first and only time in the book—lays his emotions bare and breaks down in tears. Perhaps there was sorrow mixed in those tears, remorse for the crime he had committed, and perhaps there was hope in those tears, that he had another chance to build himself up once more, no matter how long it would take.

Tied Together

I want to bring attention to the main idea that the actions of both protagonists were harmful not only because of their external effects on the world, but also because they were destroying their souls and their integrities in the process. Both works focus very much on the psychological realm of these characters, and it is truly in their redemption that one finds catharsis at the end of their journeys. Kurosawa, in his joint operations with Kitahara, alienated himself from the world after every ejaculation, and Raskolnikov, having killed the good in himself, would struggle with this fact unconsciously, until his predicament was made conscious by Sonia.

And speaking of Sonia, I also want to bring attention on the importance of the compassionate counterparts that acted as the final triggers for Kurosawa and Raskolnikov, those being Takigawa and Sonia respectively. I find it compelling that the concerned characters are both female, and it brings to mind a concept by Carl Jung called the Anima: the inner feminine side of a man. According to him, after a certain point in life, the “permanent loss of the anima [meant] a diminution of vitality, of flexibility, and of human kindness.” Takigawa and Sonia could be viewed as the externalised anima of these young men, and it is most certainly their interactions with them that made their redemptions possible: it was in developing the compassionate and humanistic facets of their characters through them that they could make themselves whole once more.

Finally, one may observe the striking resemblance between both stories’ confession scenes—in a room full of people, both Kurosawa and Raskolnikov walked in and proclaimed clearly their serious crimes. The similarities between these scenes are important because of two things.

The first of them is the fact that many people are present in the room. Such a dramatic confession would not make sense in room of only two people, because these confessions don’t concern only the criminal in question—it concerns the world around them as well. Here, Kurosawa and Raskolnikov are proclaiming the truth of their situations in relation to society: I have committed a great sin, and in doing such, I have become an exile in this world! It is in this way that these young men make their positions in the world clear and transparent—free of lies. Their confessions would have no power if there was no one to hear them.

And related to this, the second important element is that the confessions in themselves are a show of bravery and development of character. The Kurosawa and Raskolnikov of the past would not have the courage to lay themselves bare like this—Kurosawa was introverted and reclusive, and it should also be noted that Raskolnikov was a nervous wreck at the start of his story. It was only through the pain and torment they experienced that they could develop the strength to be the tellers of truth, and ultimately muster up the courage to take responsibility of themselves and to from then on live only for the highest moral virtue.

Ultimately, I find that both stories strive to point out the importance of human compassion, the importance of participating and being a part of the world, and the damning, virulent effects of living a cold, utilitarian philosophy. Both stories heavily concern those two choices: reserved, calculated rationalism, and the way of simple human compassion. In Kurosawa’s case, it was the cynicism and nihilism that many teenagers his age fall into—I’m sure you know how it was, to be an edgy teenager, or at least know someone in such a predicament. And for Raskolnikov, it was the radical utilitarian philosophy of the time he that he was caught in that Dostoevsky—through this magnificent story—would condemn for its potential to destroy the soul of every individual swept by it (this was the philosophy that lead to the Russian Revolution, and eventually the Soviet Union—where people would be treated like cattle and millions would die. In a way, Dostoevsky foresaw a lot of this). And as I’m sure you’ve already concluded at this point, the stories lean on the side of compassion: on the importance of connecting to people, the belief in the morals and ethics backed by millions of years of history, and the essential goal of striving to learn and ultimately do what is moral and good.

Thanks for reading, I’m surprised you got to the end of this whole spiel. It’s a rough essay, and admittedly a lot shallower than I wanted it to be, but if you’ve read these works already, I hope you enjoyed the analysis, and if you haven’t, I hope they’ve enticed you to try them out sometime. Take care